Federal Democracy Dollars - Who Would Pay?

Would you trade a cup of coffee for a Congress that works? How about a sip of water?

This is the third in a series of essays advocating for a federal campaign finance voucher program. In this essay I argue that because our income tax system is progressive, financing a suitably sized voucher program would impose no additional tax burden on most of the population. And even those who would pay would find the burden "modest" compared to their income.

In the first essay, I argued for a voucher program by examining the myths and misunderstandings that dominate thinking about campaign finance. It emphasized that despite all the talk of massive spending, the influence wielded by donors (of all kinds) was costing donors relatively little. But the results of policy distortion and division are threatening our democracy. Powerful support for pushing back on some of those misunderstandings is provided by Ray La Raja and Brian Schaffner in their monograph "Campaign Finance and Political Polarization: When Purists Prevail" (available as a free PDF download). It includes a short discussion about vouchers on page 140.

In the second essay in this series, I proposed details for how such a program should be configured. And presented arguments for why certain features should be present and others avoided. Questions from reviewers on that essay suggested the need for this essay.

ESTIMATING COSTS OF A VOUCHER PROGRAM

There are two kinds of costs in a campaign voucher program: (1) payouts to political candidates and organizations as reimbursement for campaign expenses and (2) administrative costs to run the program.

To be effective during its first years of operation, such as 2026, the program needs to be budgeted and structured to pay out enough money to break the pattern of exclusive control by private donors. In this essay series I use the (somewhat arbitrary) goal of providing the public at least as much money as estimated private campaign finance spending on the upcoming primaries and general election contests. This structure would reflect several factors: (1) estimates of spending on previous Federal elections, (2) estimates of voucher usage rates by the public and (3) the system used to set a value for each voucher submitted.

According to Open Secrets, the 2022 mid-term spending was about $10 billion. It looks like spending in 2024 (including Presidential spending) will be about $20 billion, so we could expect the amounts for the 2026 mid-terms to be about $12 billion (in 2024 dollars). As will be shown, my basic conclusion that cost per taxpayer would be "modest" is not significantly sensitive to the exact amount.

ESTIMATING PARTICIPATION RATES

Voucher usage rates (participation rates) are more difficult to estimate. Participation rates in Seattle's local voucher program were quite low in the first election used, in 2017. Only about 3% of the vouchers mailed to residents were used. Rates have rapidly grown in subsequent elections but are still modest (10% or less). Nevertheless, the effect of even that low participation rate has been quite satisfying to its advocates.

Interest in local elections and knowledge about individual candidates has historically been much lower than in Federal elections. And for local elections the concept of "donating to a candidate" rarely occurred to most people. Studies show that participation is much higher among the Seattle's higher income groups that were donors before the program started. Given that, how relevant is Seattle's voucher usage history to Federal elections that typically have a much higher profile? Survey data shows the public identifying Federal campaign finance as a principal problem. That suggests public interest in (and usage of) Federal vouchers would be far higher than has been seen in Seattle's local elections.

The 2022 House bill HR1 - For the People Act (filibustered down by Republicans) proposed a 3-state demonstration project that would have given us relevant participation data in 2024. In the absence of that data, the stakes seem too high to be content with a mere "demonstration" in 2026. Instead, if the point of the program is to match the power of private donations by individuals, it makes sense to adopt a dynamic approach to setting the value of submitted vouchers. I'll discuss that below.

A possible program feature that would practically guarantee high participation (eventually) was suggested in the La Raja and Schaffner book mentioned earlier: by default, assign the vouchers to a political party of the voter's choosing, such as indicated by party registration, thus relieving the average individual of the time-consuming need to evaluate candidates. This could have the additional benefit, over time, of encouraging additional viable parties to be formed. Many countries have 4 or more parties, ranging from far left to far right. With additional parties, the party structures would be more closely aligned with real divisions in the electorate. Such arrangements have been found to be more willing to form coalitions and get stuff done. Lee Drutman in his Substack essays discusses the importance of additional parties. Virtually all the democracies formed since the 2nd World War have rejected our constitutional form as unworkable and adopted some form of single legislature that elected a prime minister from among its members. Most have several parties. A voucher program that encouraged multiple parties could partially compensate some for the weaknesses of our constitutional configuration.

SETTING VOUCHER VALUE

Seattle set a fixed value of $25 for each voucher submitted. If the point of a federal program is to allow donations by individuals to match the power of private donations by corporations and the wealthy, a fixed, unchanging value per voucher may not work. At least not in 2026 or subsequent early election cycles. Instead, it may be necessary to specify a starting value and then dynamically change the value during the election season to reflect participation rates. If rates are lower than projected, the value of each unsubmitted voucher can be raised. If higher, lower the value.

ESTIMATING ADMINISTRATIVE COSTS

It is hard for me (not an expert on such things) to estimate the administrative costs. Administrative costs would include advertising, mailings, computer support, program administration, fees and interest to banks, and auditing/regulatory spending. The Federal Election Commission rules for allowable expenses are clear and well tested, as are the forms that must be used to report them. Setting up a computer system in time for 2026 would be challenging, but the structure seems fairly straight forward. Banks and auditor firms would need to be recruited and fee schedules negotiated. Bank, auditor and FEC staff would need to be trained. Opportunities for "gaming" would need to be identified and protected against. There would be the cost of developing a mailing list using State data.

It seems unlikely that administrative costs would double the total cost of the effort. But I don't want anyone to accuse me of underestimating the cost. Suppose we calculate the impact as if costs were that high in 2026. That is, suppose it took $12 billion in administration costs (an absurd overestimate, I think) to hand out $12 billion in campaign donations. For a total of $24 billion.

ALLOCATING COST TO TAXPAYERS BY INCOME GROUP

As shown below, that amount of money would impose zero to modest cost on taxpayers, with the word "modest" reflecting the "ability to pay" principle of our progressive individual income tax system. In this, a federal program is significantly different from the Seattle model, which raised the money via property taxes, a much less progressive form of taxation.

How much of that cost would be borne by various income groups? Put aside the obvious belief that a Congress that was able to work on legislation (instead of chasing dollars) would make better decisions and avoid costly policy mistakes that harm the population. Also ignore the claim made in the section 17 of the second essay that the total cost for subsequent elections would fall dramatically if vouchers were implemented. Not adjusting for either of those, if a $24 billion cost of implementation was entirely covered by using funds from our individual income tax system, without making any changes to the progressivity of our tax structure, who is likely to pay for these vouchers with extra taxes?

Our income tax system is progressive both because its rates rise with income and because it is used to provide cash benefits to poorer taxpayers. Consider the figure below, from a 2022 Congressional Research Service (CRS) report. It shows that the wealthy and fairly well off (households earning more than $200,000 a year) pay the vast majority of our individual income taxes (about 80%). Note the NEGATIVE income tax amounts for low-income taxpayers. Negative amounts result from the flow to those groups of reimbursable tax benefits that are administered via our income tax system.

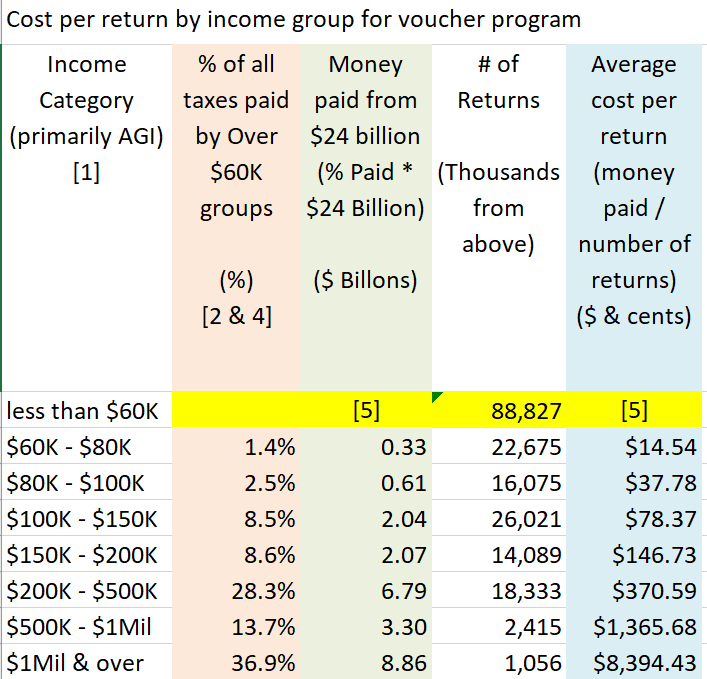

Below, in Tables 1 and 2, are my estimates for how much an average return (typically a single household) in each income group would pay out over a two-year Congressional election cycle if all the costs came from individual income taxes. Some highlights:

For households earning less than $60,000, vouchers would cost them nothing.

For households earning between $60K and $80K, vouchers would cost about $15 ($7 a year).

Households with $80K to $200K - between $40 and $150 over two years.

Households over $200,000 would pay most of the cost, as they do for all federal programs. Even so, their cost would be modest compared to their income.

My calculation uses the projected 2024 distribution of income and income taxes recently provided by the Joint Committee on Taxation. Table 1 below is an extract of that data. Negative numbers for low-income groups, using the same net income/benefit concept shown in the figure above, are highlighted in yellow. (The numbers in brackets refer to notes shown below Table 2).

Table 1 Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, pub jcx-26-24, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2024/jcx-26-24/, Table A-6

The Table 1 numbers are used to generate my Table 2, the cost impact per income group of spending $24 billion on vouchers, using that very pessimistic 100% administrative cost allowance.

Table 2 Estimate of how a $24 billion voucher program would affect taxes for various income groups (directly calculated from Table 1 as described)

NOTES ON THE TWO TABLES:

[1] "The income concept used to place tax returns into size-adjusted income categories is adjusted gross income (AGI) plus: (1) tax-exempt interest, (2) employer contributions for health plans and life insurance, (3) employer share of FICA tax, (4) workers' compensation, (5) nontaxable Social Security benefits, (6) insurance value of Medicare benefits, (7) alternative minimum tax preference items, (8) individual share of business taxes, and (9) excluded income of U.S. citizens living abroad. Categories are measured at 2024 levels." (Source: JCT, notes for Table A-6 of the Table 1 source).

[2] "Projections indicate that...taxpayers in lower income categories, on average, had a negative share of individual income taxes. Thus, on average, these groups receive more in refundable tax benefits than they pay in Federal individual income taxes." Source: Pg 19, Overview of the Federal Tax System in 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45145

[3] The totals at bottom of Col B of Table 1: The first ($2.1 Trillion) is net $ received by Government after paying refundable tax benefits. The next line ($0.1 trillion) is the sum of all those (net) benefits to lower income groups. The amount on the last line is the higher amount that higher income taxpayers pay to the government, which includes amounts to cover those benefits to low-income groups. Likewise, the positive costs shown in the last column of my Table 2 also reflect costs for vouchers that higher income taxpayers would pay on behalf of low-income groups.

[4] For each over-$60K income group, this percentage is the income in that group divided by the sum of income of all over-$60K groups.

[5] For most of the 88 million households with income less than $60K, where net income tax is negative, their share of voucher costs (the cost per return) would essentially be zero.

CAVEATS, NITPICKS & CONCLUSIONS

So, what might be inadequate or quibble-worthy with this simple cost analysis? And do those inadequacies seriously threaten the conclusion from above that the cost impact on individual taxpayers would be "modest"?

Table 2 only looks at the individual income tax, as if all the voucher costs were paid from that revenue source. In fact, only 38% of Federal outlays ("spending") currently comes from the individual income tax. Estate taxes provide less than 4% of outlays, corporation taxes about 9% while about 24% of outlays are financed with deficits. Without an explicit change in individual income tax rates to cover voucher spending (highly unlikely), some of the cost would be borne by all four of those general funding sources (including deficits). That totals 75%. The remaining 25% of outlays is financed by payroll taxes (Social Security, Medicare and Unemployment}; that money would not be used for vouchers. Thus, in our current deficit-loving, broken Congress, funding for vouchers would come in approximately the following proportions: 50% from individual income taxes, 33% from deficit borrowing, 5% from estates and 32% from corporate taxes. So the "modest" numbers shown in Table 2 are actually over-estimates of the impact on individual income taxes.

The analysis implicitly assumes that the tax and spending patterns (such as tax rates) would not change. That is certainly reasonable for the first election where vouchers are used. But the whole point of a voucher program is to recreate a Congress that reflects the will of the public and starts making good decisions again. As laid out in the first essay in this series, our current campaign-finance-built Congress has cut taxes (especially for the rich), allowed deficits to go unaddressed (except performative speeches) and fostered a fiercely divided country. A reborn Congress is likely to make many changes that cannot be captured in a simple display like Table 2. Given time, we might see a judicious combination of spending cuts and tax increases. But, until a reborn Congress can act, another disaster like the 2008 Financial Crisis could force huge cuts to Government spending without time to let "judicious" changes take effect. Currently, after two decades of "Easy Money," the Fed may no longer have the power to effectively "print gold" to bail us out of the next financial stupidity. I suspect a rational Congress would rely mostly on tax changes that reverse the flow of funds from the poor to the rich. If so, the conclusion of a future Table 2 would be substantially the same: funding would largely come from our high-income taxpayers vis our progressive individual income tax.

If administrative costs were reasonable (say, 10% instead of 100%) the costs per household would be even more modest, about half what is shown in the last column of Table 2.

In using the word "modest" I referred to the income number (basically AGI) of $200K. In some large cities, like New York City, $200K is certainly not a large income. But neither is $150 spread over two years.

The election cycle is two years. Hence, as noted, the amounts in the last column of Table 2 should be cut in two to show annual cost

This analysis treats "tax return" as equivalent to "household". That ignores the wide variety of household structures and types of returns. The results in Table 2 should be thought of as order-of-magnitude values. The modest (or zero) size compared to household income size would not be significantly affected by a more nuanced analysis.

Administrative cost is best estimated by running a pilot program. Oakland plans to do that for their local voucher program. The HR1 bill, mentioned above, was designed to start with a 3-state pilot. Unfortunately, I do not think we have the luxury of time for that. Admittedly, the program I describe in the "Details" essay is quite different from the existing Seattle program. As indicated, the modest administrative costs of Seattle's relatively simple program may not be a good guide. So, is $12 billion a gross overestimate? In the absence of a serious study, compare it to the roughly $300 billion cost of administering our entire over $4 trillion private and government health system. About 8%. So, yes, a 100% administrative allowance for a voucher program seems like a gross overestimate. Still, even if the admin cost was much higher than the $12 billion used in my Table 2, one must compare the ultimate cost to the trillions lost in transfers from the bulk of the public to the rich and to the trillions lost in another financial crisis.

So, the conclusion that voucher cost impact would be “modest” seems unshakable.

A Congress is a terrible thing to waste. So, why are we giving it up if the alternative is so inexpensive?

Best of all, forward to others who might be active in getting our political leaders to wake up and look for a real solution to our broken Congress.